Variety suomalaisdokumenteista

Harvoin saavat suomalaiset lukea sellaista herkkua mitä Varietyn erinomainen kriitikko John Anderson tarjoaa Pirjo Honkasalon ITO:sta ja Joonas Bärghellin ja Mika Hotakaisen Miesten vuorosta. Kannattaa lukaista:

ITO by Pirjo Honkasalo

Cinema as sutra, "Ito - a Diary of an Urban Priest" exists in a rarefied realm of aching spirituality and thwarted religious aspiration, echoing Robert Bresson's classic "Diary of a Country Priest" while elevating nonfiction to the level of pure art.

Cinema as sutra, "Ito - a Diary of an Urban Priest" exists in a rarefied realm of aching spirituality and thwarted religious aspiration, echoing Robert Bresson's classic "Diary of a Country Priest" while elevating nonfiction to the level of pure art.

Uncompromising, visionary work by Finland's Pirjo Honkasalo is an elusive, challenging and cerebral study of boxerturned- Buddhist Yoshinobu Fujioka, and as such, its commercial appeal will likely be limited. Reviews, on the other hand,

might just be rapturous, and "Ito" marks a substantial addition to one of the world's more considerable doc-ographies.

Best known outside Finland for "The 3 Rooms of Melancholia," which followed its 2005 Sundance appearance with a limited arthouse run, Honkasalo forsakes most conventions of standard documaking in her portrait of Fujioka. The former pugilist, twice seriously injured in the ring, has been ordained a Pure Land Buddhist priest, and wrestles with his personal sense of inadequacy and the elusiveness of divine knowledge. As with Bresson's Catholic prelate, Fujioka's relationships with the people to whom he ministers are fraught with doubt and pain. A prisoner confesses to him of having killed her husband with "my bare hands" but says she did so to protect her daughter. Still, she's plagued by regret: The child is in an orphanage, her father dead and her mother in prison. In Fujioka's face, we see infinite compassion and a fierce desire to relieve the woman's tortured mind. But we also see in his eyes -- one of which was badly damaged in his boxing career -- the frustration of being unable to say anything of consolation that wouldn't also be dishonest.

Hence, "Ito" is a fiercely religious film that's also anti-religious: How does one reconcile the idea that the suffering seek spiritual peace from a man who can't find it himself, unless he resorts to dogma and platitudes? That Fujioka is a Pure Land priest is significant; it's the branch of Buddhism that, historically, drew from the lower ranks of society due to its spiritual accessibility.

Fujioka also works in a bar, where his exchanges with customers turn the place into a confessional with booze. One overlong sequence features a transvestite lip-syncher, whose grotesque visage never leaves the screen and who serenades Fujioka until

she wears out her welcome.

Honkasalo's takes are epic; Fujioka's conversations with two female bar customers or, most significantly, his reunion with his old boxing coach -- one of the more disturbingly/exaltingly naked exchanges you're likely to see in a doc -- go on forever. Many auds will reject this, just as they'll reject the gossamer narrative of Honkasalo's entire project. But the cumulative power of the imagery and subtexts can hardly be denied. And despite the formalist rigor with which the director approaches her subject, life remains messy, offscreen and on.

Honkasalo frames her story with ancient Japanese myth, employing ornate subtitles, hallucinatory visuals, dreams and night shots of a Japan that ripples with shadows and greasy neon. But the truly hypnotic content lies in the conversations, which are lengthy but mesmerizing, accessible and intimate, and suggest that the world is inescapable and tragic, and that our salvation lies solely in our yearnings.

Ito - a Diary of an Urban Priest - Review Print - Variety.com 5/10/10 12:42 PM

MIESTEN VUORO by Joonas Bärghell ja Mika Hotakainen

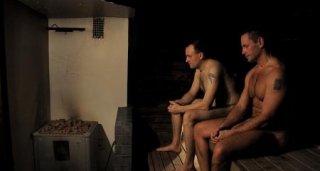

Perspiration, conversation and a certain amount of carbonation are the accessories of "Steam of Life," the best sauna movie anyone's ever likely to see, and a movie in which usually taciturn men bare their sweaty pink bods and souls. Novelty of subject matter and potent, irresistible emotional content could make this docu the same kind of hit in the arthouse it's been on Finnish television -- whose American counterpart would probably insist on covering up the naughty bits and thus diluting the raw effect of naked men stripped of their inhibitions.

Perspiration, conversation and a certain amount of carbonation are the accessories of "Steam of Life," the best sauna movie anyone's ever likely to see, and a movie in which usually taciturn men bare their sweaty pink bods and souls. Novelty of subject matter and potent, irresistible emotional content could make this docu the same kind of hit in the arthouse it's been on Finnish television -- whose American counterpart would probably insist on covering up the naughty bits and thus diluting the raw effect of naked men stripped of their inhibitions.

Sauna is shown the proper reverence in Joonas Berghall and Mika Hotakainen's strictly observational docu, which is essentially a collection of conversations captured while the subjects seem to be at their most vulnerable -- nude, wet and, occasionally, under the influence. Berghall and Hotakainen's most remarkable accomplishment is their seeming invisibility: The men in "Steam of Life" talk so naturally and easily the viewer really feels like one hot fly on the wall as the stories roll out.

Tales of sons and daughters. Marriages. Bitter custody battles. A fatal railway accidental that haunts an ex-train engineer. A dying grandfather and his worries about his wife. Prison, drink and dead children. Perhaps out of emotional self-preservation, viewers may convince themselves they're watching a theatrical performance -- because the subjects are so natural, the stories too painful, and their tellers too wounded to be confronted head-on. But it's life at its most real.

Saunas pop up everywhere in "Steam of Life" -- a converted camper trailer, for instance, or a phone booth. As a father washes his sons, he narrates a life story of mistakes and regrets, epiphanies and redemption; the small hot room becomes something sacred and transformative. Reservations melt away, and a kind of joy rises up like steam from a bed of hot rocks. Whoever says "boys don't cry" should watch "Steam of Life," which ought to be watched in a sauna, so the easily embarrassed can explain away their tears.